Indian Express

Ashutosh Varshney

3 August 2016

For the five years that this column has been in existence, it has primarily taken an analytical form. Narratives have been few and far between. This piece, and perhaps several in the future, will be acts of narration. I travel a great deal, often to faraway lands. Sometimes before my instincts as a researcher kick in, the lands I visit invoke a desire to report the life on the street, the routine conversations in trains and buses and on planes and ferries. V.S. Naipaul once said that one learns a lot by observing, talking and simply seeing. The world of data can learn a fair amount from the invocation of the eye and the flow of everyday conversations.

I recently returned to Bengaluru after nine days in China. I visited Beijing and Shanghai after four years, and Hangzhou for the first time. Beijing and Shanghai, of course, have a global reputation. Less known globally, Hangzhou has been a centre of literature and culture. To this historical reputation, mainly confined to Greater China, a new international landmark has recently been added. The G-20 summit will take place there in September. Also, since the late 1990s, Alibaba, an internet-based company scaling new global heights, has been headquartered in Hangzhou. Jack Ma, Alibaba’s founder and one of the richest men in the world, was born in the city. He is a former English, not engineering, major, emphasised my guide to the Alibaba campus.

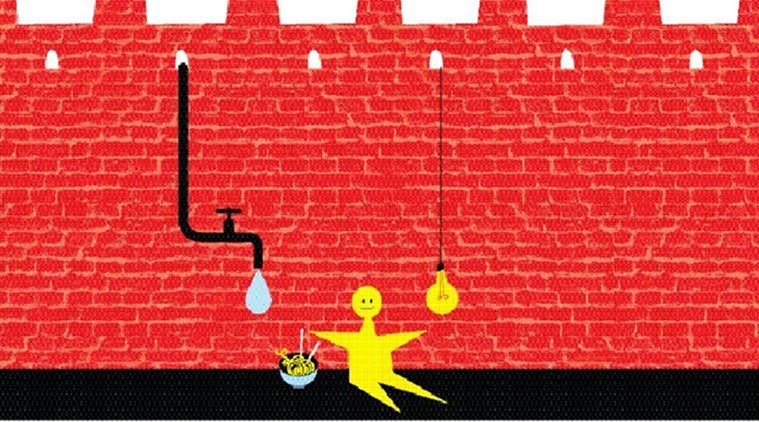

Google, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and the New York Times are among the sites already banned in China. Illustration by: C R Sasikumar

Google, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and the New York Times are among the sites already banned in China. Illustration by: C R Sasikumar

I was invited to Beijing and Hangzhou to give lectures on India’s democracy — its achievements and deficits. The interest shown by my audience in democracy came as a surprise. As expected, some in the audience did argue that economic development should always be given priority over democracy and India’s embrace of democracy was a horrible mistake. But most people heard my arguments with interest and curiosity.

Too much, surely, should not be made out of two seminars, but this experience is consistent with what The Economist recently wrote in a special feature on the Chinese middle class, up from a mere 5 million households in 2000 to 225 million now. It said that a new aspirational space for freer discourse, beyond the pursuit of prosperity, has opened up in China. One should, of course, not rush to infer an intense craving for democracy from this. The government, in any case, has heavily cracked down on civil society and the social media. Xi Jinping’s regime is concerned that China has already become too dangerously liberated, given historical standards of habitual deference to the Communist party. China is certainly less free than it was four years ago, but its citizens’ desire for freedom may well be greater.

A big question has unmistakably emerged. Can China’s Communist government successfully control the flow of information in this day and age? Google, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and the New York Times are among the sites already banned. But people easily buy Virtual Private Networks (VPN) online, which allow access to blocked websites. My Alibaba interlocutors say that out of the 600-odd million internet users, only an estimated 10 million Chinese use VPN, so it is not threatening to the Chinese state. If most of your internet needs can be met by the Chinese substitutes for Google, Facebook and Twitter, the threat might not be great in the future either.

But freedom is becoming relevant in another sense. In the late19th and early 20th century, many Chinese migrated out to escape poverty, forming ‘Chinatowns’ in the US, Canada and even one in Calcutta. Now, rich and middle class Chinese are also leaving because they are not sure their assets will remain safe. Four years ago, I did not encounter so much angst about what the government might do. There was greater belief in the government’s sincerity.

The mistrust of government may not be evenly spread geographically, nor might it undergo a linear decline in the future. I report only conversations, not nationwide data or predicted trends. Given our conceptual understanding of how communist polities are institutionalised, a party that brought 700 million people out of poverty since 1980 is unlikely to lose mass legitimacy any time soon. The party controls the armed forces as well. An alternate centre of power cannot easily emerge. Despite economic liberalisation, communist monopoly over power is complete.

Anna Gryzmala-Busse, my former colleague at the University of Michigan and co-panelist in Beijing, added another reason. Based on evidence from eastern and central Europe, she argued that where communism and nationalism were fused together, it was hard to overthrow communism; where communism was imposed on the nation, the unravelling was easier once the Soviet Union collapsed. In China, nationalism and communism are inextricably interwoven. The Soviet Union did not force communism upon unwilling and hapless Chinese leaders. Mao was his own master, not a Soviet supplicant.

Let me turn to the economy. International economic circles might have commented profusely on the Chinese slowdown and on economic growth rates, repeatedly noting India’s recent march over China. Neither argument appears to have impressed Beijing intellectuals.

China’s GDP has crossed $10 trillion, they say. Even if China’s growth rate is 6.5 per cent per annum, it will continue to add more to GDP each year than a 7.5 per cent-8 per cent growth rate for India, whose GDP is still $2 trillion. India’s economy has a long way to go before coming close to China.

I also ended up doing something that foreigners rarely get the opportunity to do. Guided by a Chinese scholar of urban slums, I visited a slum in Pudong. Slums and shanty-towns have historically accompanied the rise of industry and cities, but it is usually argued that China has defied this pattern. Its urbanisation is marked by a “relative lack of slums”, says Jeremy Wallace in his book, Cities and Stability.

While that may be true, it is also noteworthy that unlike the ubiquitous slums of India and Brazil, China has kept them hidden from the eyes of the visitor.

“How long does this slum get water and electricity each day?” I asked. “Twenty-four hours,” replied my surprised interlocutor. India may be far ahead on freedom, but how long will it be before it can guarantee unbroken supply of water and electricity to all?

*The writer is Sol Goldman Professor of International Studies and the Social Sciences at Brown University